2025. December 10.

Maria Vanyovszki

Transylvania – Passau – Berlin – New York. Ottó Nagy-György started out in Gyergyó, attended secondary school in Marosvásárhely, then moved to Passau, from where he went on to Berlin. He is currently studying fashion design there. One of his projects has already taken him all the way to New York’s Times Square, as Csinszka, who is also from Transylvania, appears in the international Spotify Equal campaign as the Hungarian ambassador wearing an outfit he designed.

Nagy-György’s work, created under the name TRANSSPIRIT, is, like Csinszka’s music album, a deeply personal apotheosis of Transylvanian identity.

How do you remember your early childhood? What kind of boy were you back then?

When I think back to my childhood, that time seems to be covered with a warmer filter, with brighter colors. I have a calm nature, but at the same time I am always looking for mischief to get up to. I play a lot outside in the yard with our animals, inventing games for myself. I like to play with my sister, toy cars leave me cold. I love drawing and painting most of all.

You mentioned your grandmother was a hobby painter. How did her creative spirit and the drawing sessions you shared with her influence you?

When I drew with her, I was more courageous in choosing more complex motifs, which were actually quite challenging for a 4- or 5-year-old child. It didn't even occur to me, because her presence gave me creative security, and somehow we always managed to "make it work" in the end. That gave me self-confidence.

What was it like to experience the world of clothes and women up close while spending time in your mother’s thrift store?

It was interesting to observe the different types of customers: some were just browsing, others were looking for a specific item, but you could never really know if the visit would be fruitful, because shopping is like buying a cat in a bag. You could see the pensive expressions on people's faces as they pulled out individual items: Does this suit me? Is this me? Can I be this? Should I try it on?

If they liked it—and if the music playing in the background matched—their shopping fever would intensify. This moment struck me several times, especially with women. In my mind, only a fashion show could have rounded out this picture better.

When did you first realize that fashion would become your profession, and how did that realization come about?

I think I started putting together my own daily outfits when I was in kindergarten. I always observed what others were wearing and how I presented myself. At the end of eighth grade, I applied to the art school in Vásárhely because it offered a specialization in textile design. That's when I realized that I wanted to pursue fashion design through art and make it my career.

You’re from Gyergyószentmiklós, lived in Marosvásárhely, and then moved to Germany at 17. How do you remember these changes, and what was it like to move from one world to another?

Moving to Vásárhely felt like a big step at the time. There was still something there that I knew from Gyergyó: a kind of homely, Székely comfort, but at the same time it was more open and international, which was very exciting. In Germany, however, I no longer felt the presence of the previous cities at all. This was no longer a step, but a milestone.

At home, I felt different, but here I felt like an alien.

I would compare the change to replacing an impressionist painting on the wall with a pop art poster. All of its components are separated from each other by clear contours, yet it works and appears unified. It is strongly characterized by the West, which is attractive—but the question is, do I have this kind of superficiality in me?

Model: CSINSZKA - Photo: VICTORIA PERGER

Model: CSINSZKA - Photo: VICTORIA PERGER After 2017, you lived in Passau and then continued your studies in Berlin. How did you experience integrating into these new environments, and when did you start to feel “at home”?

I think it was when I started speaking German more confidently that I truly began to feel present. Through this, I discovered a new space that eventually became home.

Your college project sparked your interest in your Transylvanian cultural heritage. How do your professional development and your search for identity connect?

Yes. Second Skin is one of my projects that was created under the supervision of Hussein Chalayan.

As part of this, I began searching for inspiration, exploring, and then I went so far that I eventually stepped outside the designated framework—and somehow found my way home.

Can you tell us more about your interpretation of Second Skin? What does this “second skin” represent for you?

My second skin is my culture — it lives on me and transforms with me.

It’s like fine dust that settles unnoticed on my hair: you can comb it, scrub it, wash it — yet it never disappears. It simply mixes with other particles until it becomes a new alloy.

But this second skin is not a shackle — it’s a living material. It reacts constantly, changes with me and at the same time preserves something of my origins. It also acts as a weight because it is always with me and cannot be taken off – and yet it is one of the most essential components of my personality.

When we apply this to a piece of clothing and put it on, it is as if we were covered in protection: a familiar, comforting feeling. It carries our culture and the legacy of our ancestors—the rokolya, the suba, Sunday mass, the smell of the colour green, the stars, the myths, and perhaps even the nature of the bear.

What principles have you identified along the way? How do you think the “dust” or “grains” we carry from our roots influence us, even when we don’t consciously choose them?

I’ve noticed that in many layers of our transylvanian culture, we act according to the principle of sustainability, whether consciously or instinctively. From a global perspective, this can almost be seen as a rebellion against a wasteful society. Treasures, clothing, and objects preserved and passed down as family heritage, for example, were made to be durable and timeless, meant to be used for a long time.

Your work reflects Székely traditions, yet it also incorporates strong conceptual and performative elements. How do you combine tradition with recycling and the standards of haute couture — by which I mean high-quality design and craftsmanship?

Not everything has to be brand new for something fresh to be created. I believe that newness lies not in the raw materials, but in the work process, recycling, and the techniques that are chosen.

These are what give the work its distinctive quality, the sense of novelty that emerges in the final result. For me, this is further supported by conceptual thinking, which allows tradition to be translated into a contemporary language.

We’ve discussed Marina Abramović and her influence on you. What does her journey and work mean to you, how is it built into your fashion language?

I am deeply inspired by the directness and self-identity that define her personality and art. Although she grew up in the Balkans rather than Transylvania, this background leaves a clear imprint on her work. Experiencing her art is not easy, but it is intense and powerful. Her raw honesty—for example, not sugarcoating her childhood or the realities of life in Eastern Europe—resonates deeply with me.

You also think about masculinity and femininity across a broad spectrum. As a fashion designer, what questions are you exploring about gender and clothing?The focus here is on the spectrum, even if it has traditionally been labeled blue and pink. Our gender—our social gender and identity—has never been more fluid or open to reinterpretation. I’m not suggesting this should be imposed on anyone; it’s a deeply personal matter.

It is a personal, internal transformation that can free the self from certain roles.

As a fashion designer, I try to playfully incorporate this expression of liberation into individual pieces. As a result, the length and dimensions of the pieces I create may differ from the norm, and if someone notices, for example, that the feminine side is emphasized in the outfit I created for my masculine-looking male model, then I have achieved my goal.

What inner questions gave birth to TRANSSPIRIT? And what answers did you find about yourself along the way?

Once I had clarified the concept of the second skin and found a direction, I became interested in the symbols of traditional Székely clothing and the meanings they carry.

What do the colors symbolize? – What messages do the embroideries convey? – What might the thickness and colors of the stripes on the rokolya indicate? (The stripes varied from village to village.) – What elements were typically feminine, and which were masculine? – What was considered acceptable, and what was seen as provocative? – How can these traditions be interpreted from today’s perspective? – And what did all of this look like before the Ceaușescu era?

The TRANS(silvania)SPIRIT collection was born from these questions and discussions with others.

The rokolya, the sheepskin coat, oversized silhouettes, the blending of masculine and feminine—how did you reinterpret these traditional elements in a contemporary, Generation Z visual language?

I think this combination has a power dressing quality, and it’s something anyone can wear. The skirt — a feminine touch — breaks up the proportions and stretches them vertically, elevating the wearer to a higher level. The suba — masculine element — carries a protective character, much like a shepherd in the field who guards and guides the flock.

How did you connect with Csinszka, and what made you feel she could be the ideal “voice” for this outfit?

I first noticed Csinszka online and started following her. That night, around half past one, we messaged each other for the first time—at exactly the same moment.

I told her that I could see her in TRANSSPIRIT, and she replied that she could see herself in it too.

It was a very special connection from the very beginning. What does it mean to you that your work is worn by someone who, like you, is from Transylvania and now lives in another country?

For me, when someone who is also from Transylvania but lives in another country wears my work, it means that the piece somehow comes to life again. A more concentrated image is created, in which I recognize myself, and perhaps others do too? It gains additional meaning because we share something in common, which gives us an unspoken sense of trust. In this situation, I felt that I was truly understood and seen through the clothes.

I see that when fashion finds a way between two people, it can create a real connection.

Model: CSINSZKA - Photo: VICTORIA PERGER

Model: CSINSZKA - Photo: VICTORIA PERGERIf you had to sum it up in three words, what would you say are the core values of your design?

Sustainable – Timeless – Sensual

In the future, would you rather build your own brand, or work for a major fashion house? Balenciaga, Tom Ford, or perhaps Thom Browne or Robert Wun—what would you be looking for in that experience?

I can imagine having my own brand in the near future; and until then, I’d gladly absorb knowledge at Tom Ford — perhaps in Italy.

What feeling, experience, or world do you aim to convey through your clothes—beyond the textiles themselves?

Perhaps intimacy within a mystical landscape, a sense of belonging, comfort, and confidence.

If you look back at the Székely boy who visited H&M for the first time in Marosvásárhely, what would you say to him today?

Don't worry about what other people think of your appearance. Most boys will be wearing the same thing you're wearing now in a few years anyway.

What has been your most important realisation about yourself in recent years?

Recognizing and setting my own boundaries.

If you had to describe yourself with a single image — who are you?

If I were to depict myself in a single image, I would be a copy tree. The notches, symbols, stripes, and layers on it are recognizable at once, but never completely readable. I am not only made of wood, but also of an alloy, metal and wood. I am not only carved with precise lines, but also hammered and forged.

I must be heated to be moldable, and it is exactly this intensity which brings this body to life. Like an antenna, I give and receive, transmitting what comes from the past, the present, and the future.

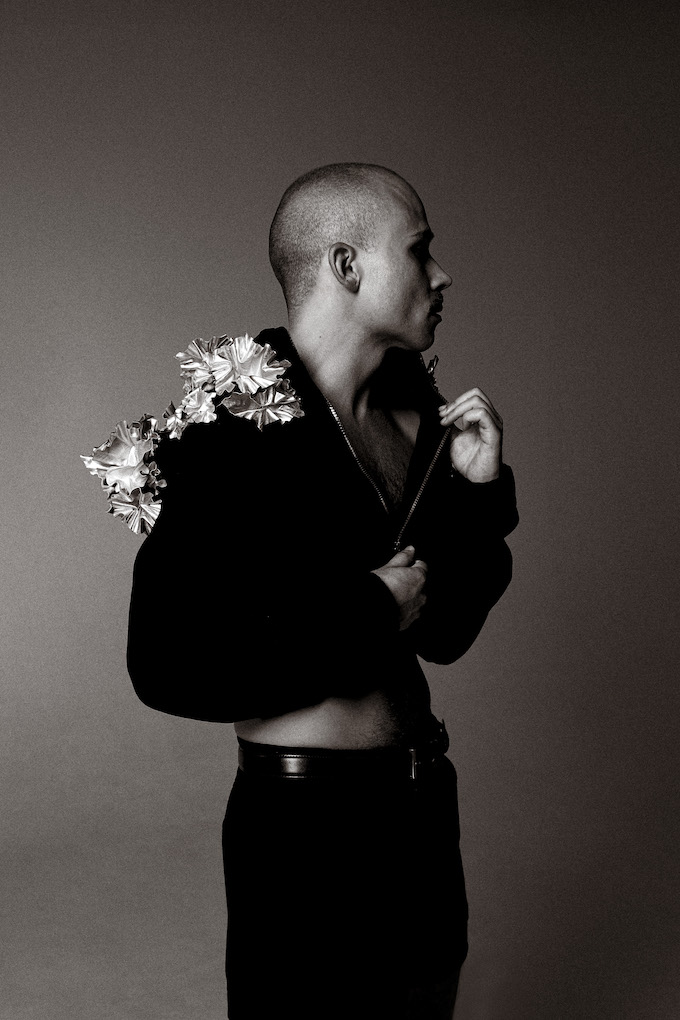

Model - Photo: OTTÓ NAGY-GYÖRGY

Model - Photo: OTTÓ NAGY-GYÖRGY